The History of Labour Day, and the Summer of the Strike

It’s the compromise that prevented a war

The first Monday of September is a vastly undervalued and overlooked holiday.

Often, we think of it only in terms of a long weekend. The end of summer and the beginning of fall. A day off to hang out and spend a day outdoors before the weather grows cold once more.

But this is an important day in history for a very different reason.

We should instead recognize it as the day to celebrate the working people of North America; to memorialize and reflect on the contributions and efforts that they make to keep society running.

Labour Day, as we call it, has been a holiday in North America for a long time. In the United States, Labor Day was officially signed into law as a federal holiday on June 28, 1894. It followed a series of absolutely brutal conflicts with striking workers over the horrific conditions of the Industrial Revolution.

In Canada, we originally celebrated a version of the same holiday in the spring, like many other countries do around the world. We did so in commemoration of the Toronto Trades Assembly strike of 1872, and the founding of the Canadian Labour Congress in 1883.

We later officially shifted the date to September so as to link the celebration with the workers in the States.

Labour Day is the time to fight for the rights of workers, stand in solidarity, and demand better pay. It’s also a day to remember that it used to be illegal to do that.

It’s a day to remember that the rights we take for granted are rights that were paid for with blood.

In the year of 1921, from August 25th to September 2nd, one of the largest armed uprisings on American soil kicked off. On the slopes of Blair Mountain, over 10,000 coal miners went on a violent strike: raising weapons against a force of 3,000 lawmen and strikebreakers hired by the companies they worked for.

To date, the scale of this conflict is second only to the American Civil War.

Following the public assassination of a police chief who stood in sympathy with the coal miner’s union, the disgruntled workers refused to accept further mistreatment.

They’d had enough of being forced to live in company towns, being paid in vouchers that had no value outside of shops owned by their bosses. Their pay was docked for housing and medical care for injuries sustained on the job. They were kept in line by armed guards, paid by the companies to ensure compliance.

They’d had enough.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was only one among many conflicts in Virginia at the time. The West Virginia Coal Wars were numerous and often deadly, and sporadic violence kept breaking out for nearly a decade.

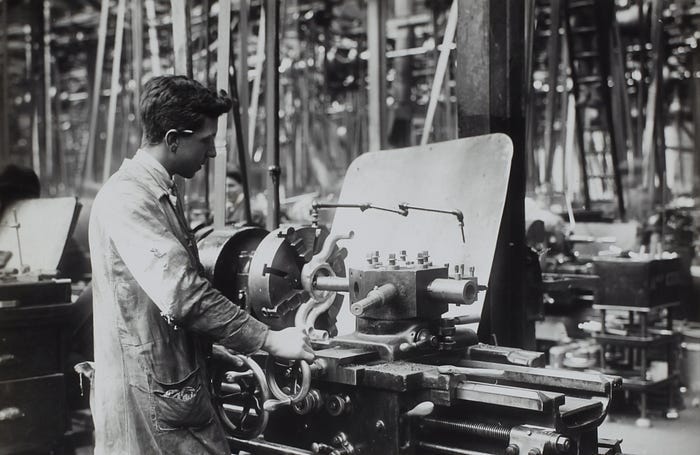

In the early 1900s, labour laws in the States were so lax as to be completely inconsequential. There was no age requirement, and children as young as 10 could commonly be found working in factories. Racial segregation was the norm. Workplace safety regulations were laughable, and often entirely ignored.

There was no federal protection for unions, and so the bargaining power of workers was limited. When attempts to protest and strike were made, they were often suppressed with brutal violence.

People were killed on both sides of the line — and how could anyone be surprised by that? In desperation to make money and feed their families, mistreated and left in debt to their employers, what other recourse did workers have?

Before worker’s rights were established, it wasn’t unheard of for bosses to be left crawling with a broken leg, or to find their houses burned down in a labour riot. It was equally common to find striking workers building barricades and standing their ground with guns around their place of employment.

Peaceful strikes sound pretty good in comparison.

Earlier, I mentioned that the miners lived in company towns. If you don’t know what that means, prepare to be angry. You don’t see them anymore because they are unbelievably illegal today.

Imagine waking up to go to work, and the house you live in is owned by the company. You put on your clothes, which you got from the shop down the street — also owned by the company.

You eat your breakfast, bought through the company, and you walk down the street to the worksite in your shoes — bought from the company. You spend your day working, and you receive your pay.

Your doctor is provided by the company, and you have to pay for him through your wages. Same as your house. Neither is provided for free — and for that matter, nor is any equipment you need. You’ve got to pay the company for that, too. Even your church was built by the company.

You live in the gold standard of gated communities, though. You’ve got fencing and armed guards. They say they’re there to keep you from being exploited by shady salesmen from the outside, but you know better.

They’re there to keep you from kicking up a fuss. They’re there to keep you where you are.

Not that you could leave anyway; you have no money. Your company scrips can’t buy anything anywhere else. In some towns, the costs of housing are so insane that you’re not being paid at all. You’re in debt to your employer.

You are a slave in all but name.

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store — 16 Tons, by Tennessee Ernie Ford

Think about the basic rights you have as a worker in North America.

Your five-day work week — that’s a union victory, won with strikes and protest. Weekends are a thing because workers fought for them. The same goes for 8-hour days and overtime pay.

Child labour laws were fought for. Workplace safety was fought for. Compensation and pay were fought for. The right to unionize at all was fought for.

They were just as hard-fought as women’s suffrage, or the ‘end’ of slavery in America.

These are not things that were graciously given to the people by corporate interests — don’t for one second think that your rights are valued at all above profits. And we know they aren’t, because to this day they’re still fighting to claw them back.

Child labour laws are being loosened. Not that the protections in place prevented exploitation in the first place, but now they’re trying to strip away the legal barriers that kept it quiet.

We know that big corporations could not care less about workplace safety, either. Do you know how many times Amazon has been cited by OSHA for putting their employees in jeopardy? Given the absolute pittance of a fine they’re issued for it, I doubt the company gives a damn.

So long as they make more money than the court fines cost them, they’ll keep doing what they’re doing to turn a bigger profit.

Today, strikes for equal pay and better working conditions are becoming commonplace. Since the Covid-19 pandemic was declared, workers have been pushed to the brink of tolerance and beyond.

Canada’s seen some incredible protests in the past few years, including a 22,000-strong strike by CUPE members in my home province. I know many people who were part of it, and I’m so proud of what they managed to achieve.

They’re still actively battling for worker rights. They deserve all the support they’ve gotten, and more. But it’s not just in Canada that we’re seeing an escalation in this battle.

Remember the Hollywood strikes? On August 31st, 2023, the California State Treasurer sent letters out to Hollywood companies to beg for an end to the writer’s strike. It was decimating California’s funding.

The Writers Guild of America had been on strike since early May. A second strike, that of actors represented by SAG-AFTRA, later joined them on the picket line and ground the entire industry to a standstill.

It dominated the news for months.

I read an excellent piece at the time about income inequality and the reality of life for people living and working in Hollywood during the strikes. The refrain is familiar; the company owners rake in cash while the working class struggles to make do. Exploitation is not industry-specific.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a supposedly high-class writer or actor in Hollywood, a minimum wage worker in downtown Detroit, or a nursing home attendant in Moncton. The fact remains that to the people above you, you’re expendable.

Workers are machines that churn out profit for the company. Nothing more, and nothing less. That’s all we’ve ever been, and as long as we accept the status quo that is all we’ll ever be.

So, as we celebrate Labour Day this year, let’s take a moment to examine our situation. Really look at it. Really think about whether or not you’re truly happy in your job, and if it could be improved.

What would it take to make your workplace somewhere you don’t hate? To ensure that you feel fairly treated, well represented, and not exploited?

Think about it, and then talk about it with your coworkers. Because if there’s one thing that has been proven time, and time again, it’s that when workers come together for a common cause, they get shit done.

Solidarity wins.

With things going the way they are, we can expect more labor strikes in the near future.

Labour Day here in New Zealand is celebrated on the 4th day in October. In 1840 carpenter Samuel Parnell in Wellington NZ fought for the right to have an 8 hour working day and won.